Software-Defined Storage

Infinidat: Software-Defined Storage (SDS): How Pre-Integrated SDS Stacks Up Against Software-Only. Executive Brief.

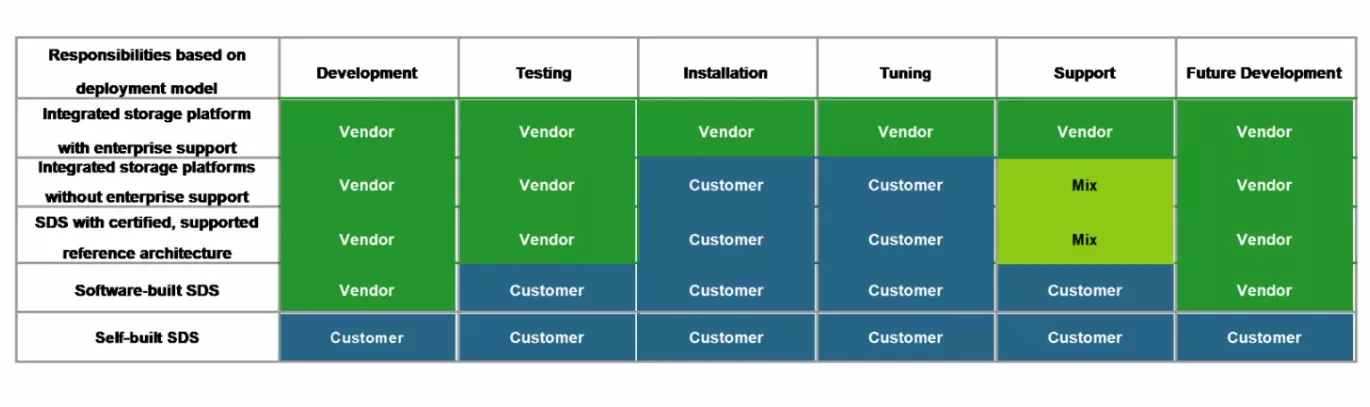

Introduction Companies have set goals to add “software-defined” to their data center lexicon, causing some storage vendors to jump on the bandwagon with the software-defined label as a way to be competitive in the market. But can these vendors deliver all of the benefits of a software-defined storage platform? Do they truly increase flexibility, drastically lower cost, and provide the scalability and ease of use that are the goals of this new paradigm? At the end of the day, the goal of software-defined storage is lowering the “Ex” factor” (CapEx and OpEx) and improving a company’s bottom line. Organizations want to drive synergies across their existing procurement teams to get the best price for the hardware they are buying — increasing CapEx utilization. They also want storage solutions that dramatically reduce operating expenses. Unsurprisingly, they want this without sacrificing the high performance and reliability they are used to getting from proprietary storage solutions. Given this, how can organizations realize the benefits of software-defined storage, stay focused on their core competencies, and maintain their competitive advantages, without spending tremendous effort or dollars developing storage systems. The goal of software-defined storage is lowering the “Ex” factor” (CapEx and OpEx) and improving a company’s bottom line. Proprietary Hardware Slows Innovation A decade ago, most storage systems were proprietary platforms. Storage hardware vendors designed and manufactured custom controllers and ASICs to run their arrays. They would design and manufacture proprietary backplanes in order to achieve the best possible performance. They would then write custom software to communicate with this custom hardware in order to provide the highest level of feature/functionality and reliability. In addition, each system variety would have its own expensive, proprietary management platform. In this way, they ensured their storage products met the competitive demands of Open Systems computing — yet without actually being “open” at all. That dynamic, however, is changing. Proprietary hardware has become very expensive relative to commodity hardware and innovation cycles are longer, creating challenges for legacy storage vendors. Key metrics businesses pay attention to now are “time to innovation” and “time to market.” Organizations need the flexibility to develop and deploy new products and services quickly. As demand for more scale, higher performance levels, and new storage services grow, increased development resources are required to address those needs. The result is that it takes much longer to get new, improved products into customers’ hands using proprietary hardware, slowing innovation. The Creation of the Software-Defined Market The entire IT industry has been progressing toward “software-defined” starting from the rise of general-purpose computing. Storage is no different. Right around 2000, adopters of hyperscale computing realized that “off-the-shelf” Intel hardware was capable enough to be used as the building block for storage systems — at a much lower cost than they were paying for proprietary storage arrays. Companies like Google decided that they didn’t need to design cache cards, fabricate their own chips or develop sophisticated backplanes to build a storage system that met their needs. They could simply buy inexpensive servers and leverage emerging global supply chain economics for computer hardware to build their own storage systems at a much lower cost. The consolidation could also allow them to run other workloads on the same hardware depending on demand patterns. In order to do this, however, they created their own software layer that allowed these servers to function as a scalable storage platform, and to shift the reliability burden inherent in commodity products. In addition, and not taken into account as a part of the technical capabilities is, while the perception is “low cost” because the cost of the servers is low, the number of servers grows due to the number of copies of data required to sustain high availability, hence the OpEx around data management and power also increases. As this new paradigm gained attention, the incumbent storage vendors opted to fight fire with fire by offering subsets of their product portfolios that were based on low-cost, commodity hardware as well. In the mid-market, this led to the use of Intel-based systems for new storage array platforms. However, the vendors stipulated that these new storage systems could only run their software on very specific hardware, which was procured through supply chains the vendors controlled. As an example, in order to get NetApp-like features and functions, and support from NetApp, the ONTAP software can only run on devices that NetApp procures and “certifies.” The fact of the matter is that software -defined storage is quite difficult to get right, and it introduces a high amount of risk and cost. In this scenario, the storage vendors would buy two simple x86 servers and a few disk drives at relatively low cost, then package with their software, however, they would charge hundreds of thousands of dollars to the clients, in line with traditional storage pricing practices. The vendors’ software and responsibilities for integration, testing, and support certainly added value, but in general the shift, first and foremost, allowed them to expand profit margins. Naturally, this situation did not sit well with many storage consumers, who wanted to benefit from the same flexibility and cost savings that Google and others were seeing when it came to storage. They wanted the ability to decouple storage services (the control plane) from the hardware (the data plane) because they believed they could get similar hardware for much less money and run storage software on it, ultimately driving down their costs in the data center. Meanwhile, the bar for free/open-source storage software stacks was getting higher. Thus, interest in software-defined storage began to take off. The Big Problem with Most Software-Defined Storage There are certain challenges that aren’t readily apparent looking at the “Google Solution” for storage. The fact of the matter is that software-defined storage is quite difficult to get right, and it introduces a high amount of risk and cost. In order to implement a “Google Solution” for storage, an organization needs to develop, test, install, integrate, tune, and support the new system in its entirety. There is a great deal of hidden cost in all of those areas. In addition to requiring highly skilled people to build out the solution, an integration lab is also necessary to put all of the technology together and test it to ensure it can deliver the required reliability and performance, and funds must be committed for ongoing tuning and maintenance throughout the deployment lifecycle of the solution. In addition to those direct costs, this risk can translate into downtime for the corporation if problems occur. The latest industry information suggests that the cost of downtime for the Fortune 1000 is estimated to be between $1.25B and $2.5B and the average hourly cost for an infrastructure outage is $100,000 per hour. The support burden also increases for the organization, especially if the choice is made to self-support a platform based on open source software. Even if the organization chooses to use commercial software, they should get accustomed to calling customer support and having the engineer on the other end of the line say, “Well, it looks like the software is working fine, better speak to the hardware vendor.” Most organizations require high performance and reliability from their storage, however, most don’t have the expertise, time, equipment or lab space to build a storage solution that meets these criteria. Organizations considering implementing a software-defined storage model from scratch may not realize that Google is home to a number of highly experienced (PhD) computer scientists that spend tens of thousands of hours developing their own specialized, highly tuned storage software to run on commodity hardware. Additionally, the solution is purpose-built for their very specific business needs. Google makes an enormous investment in terms of the people, equipment, and lab space needed to build and test this software. This is their IP and a part of what makes Google, well, Google! This is not comparing software-defined storage to Google, but only using it as an example of what it takes for a company to build such a platform. Investing in storage software is core to Google’s business, however, this is likely not the case with most organizations, and may actually be contrary to their goals of minimizing IT investment to support a given set of business needs. Yes, most organizations require high performance and reliability from their storage to support a number of different applications, however, most don’t have the expertise, time, equipment or lab space to build a storage solution that meets these criteria, while also lowering the overall cost of storage. In fact, the time, effort and complexity of trying to build such a solution may distract or delay the organization from achieving its more strategic goals. Upon realizing these challenges, most organizations skip out on completely homemade software-defined storage, and turn their attention to commercial software layers offered by a variety of players — the likes of EMC ScaleIO, IBM Spectrum Scale, or Red Hat Ceph. These solutions do allow clients to remove direct development costs of building their own storage software layers, but most of the other key SDS challenges remain. The client still has to test, install, integrate, and tune the system, and support remains a “hot potato” game between the server hardware vendor and the storage software vendor, possibly with the operating system vendor thrown in the mix too. Clients can remove more of those challenges by working with a third-party outsourcer, integrator, or certified reference architecture, but many times those options add enough cost back into the solution that it’s probably worth looking at pre-integrated storage systems again! Is Pre-Integrated, Software-Defined a Better Way? Given the promised benefits of software-defined solutions and the challenges involved in implementing and managing such solutions, can a pre-integrated model provide a better answer? There are a number of factors to be considered and it helps to first understand the responsibilities with each potential deployment model, shown in the below diagram:

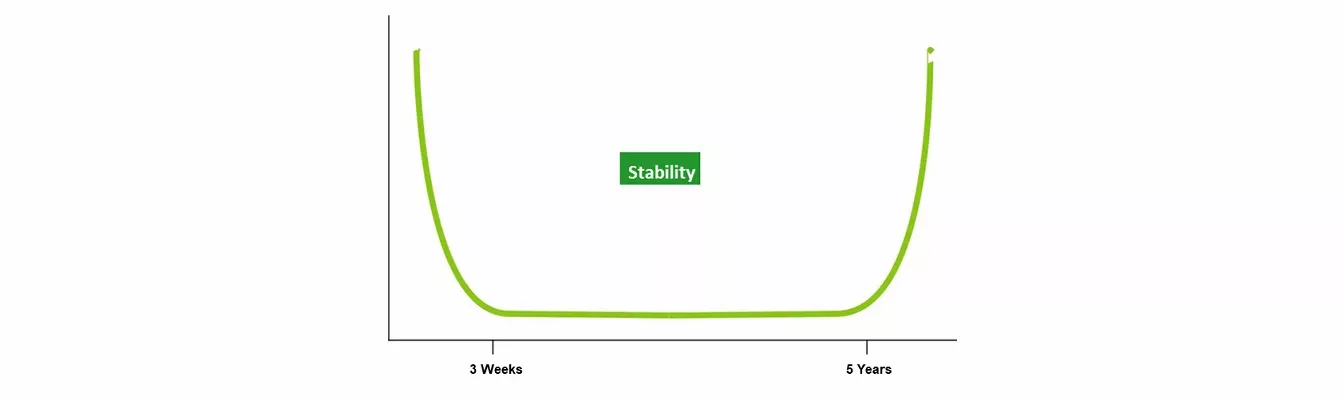

Focusing on the SDS deployment models: a software-only SDS solution where the client buys off-the-shelf hardware and software will require effort from an integration perspective. An organization may love a particular software platform, but they then need to check the vendor’s hardware compatibility list (HCL) to see which hardware can support the software. If the client doesn’t happen to get great discounts on the hardware required for the SDS platform, then it defeats the purpose of moving to an SDS model. Once the hardware is procured, it needs to be brought up to the SDS vendor’s specs: right OS version, right firmware versions, etc. While vendors try to keep their HCLs as up to date as possible, the only way to really know for sure if there are any issues with the solution is through the arduous task of trial and error to ensure all components can talk to one another and the software properly. All of this adds cost to the solution and increases deployment time. Once the software is installed and the system is built, it first needs to be tested. Organizations will need their own “QA” environment to specifically test hardware, firmware, and software combinations. By way of example, INFINIDAT has revealed major issues with very specific hardware / firmware combinations that only hours of sophisticated testing were able to find. Customers without these test environments will find these kinds of issues only once the system is put into production, when it is too late. Another reason organizations buy a software-defined solution is to have more flexibility to align the software capabilities with how they do business. However, most storage software requires significant tuning to accomplish that goal. Storage engineers and application engineer(s) need to get together to make sure they configure the software properly to get the most out of the new system in order to meet their business SLAs. A big part of this process is again trial and error and testing. Organizations need not only the new equipment, they also need a test or QA lab alongside their production environment. Finally, once everything is working well, at some point inevitably something will change or new features will be required in the application that will require a change in the storage layer. At that time, more configuring and testing will need to take place before the updated solution can be turned on and deliver value to the business. All of this will occur on an ongoing basis, because many storage software vendors are moving to a “continuous delivery” / DevOps model which means very rapid release iterations. (2) Regardless of whether an organization actually realizes any value from moving to a software-only SDS approach, an SDS solution that is delivered to the customer as software-only unquestionably requires incremental expertise, space, money for equipment, and time. All of these affect an organization’s budget as well as time to market or competitive advantage, and it isn’t just a one-time impact — every patch cycle carries with it a new set of challenges. A pre-integrated, software-defined storage solution removes 100% of the burdens outlined above. (2) http://www.juku.it/en/storage-product-development-getting-worse/ Pre-Integrated, SDS You Can Trust and Afford INFINIDAT’s fundamental belief is that clients should only need one horizontal storage platform to give them all of the benefits they expect from the software-defined paradigm— flexibility, agility, reliability, performance, usability, feature/functionality, and most of all, affordability. The INFINIDAT storage software architecture was created with these benefits in mind. INFINIDAT’s fundamental belief is that clients should only need one horizontal storage platform to give them all of the benefits they expect from the software-defined paradigm. The INFINIDAT storage software architecture is designed and built to be hardware-agnostic but is pre-integrated with commodity hardware to deliver the most reliable storage array on the market. There isn’t anything about the design of the software that ties it to any hardware component in the InfiniBox™ storage array; as an extreme example, INFINIDAT software is running in public clouds today for selected environments. However, INFINIDAT takes both the notion of ‘software-defined’ and the trust required to store organizations’ most important assets, their data, seriously — and the best way to address those needs today, in most cases, is with a pre-integrated, software-defined platform. Rigorous testing and quality assurance are key components of any successful pre-integrated software-defined approach. On day one, INFINIDAT built out a 120PB QA lab using millions of lines of QA automation software(3) to design, test and work through thousands of bugs and obstacles. Through extensive testing, the company has uncovered hardware problems from the manufacturer before they could make their way into production. INFINIDAT is also able to successfully work through the hardware and software integration woes including firmware anomalies and hardware issues; customers who implement software-only SDS solutions are challenged to discover and resolve these kinds of anomalies and issues on their own. One way SDS vendors try to minimize the risk is with a hardware compatibility list (HCL). However, the constraint of only working with ‘certified’ hardware flies in the face of a “true” SDS solution — yet still leaves the customer to deal with all of the integration challenges. Finally, INFINIDAT is able to catch hardware instance issues. These are issues where there are not necessarily bugs with the hardware, but a faulty or bad batch of drives is installed, or HBAs are not seated properly, or faulty memory, etc. These are not predictable issues, however, they do happen. A pre-integrated, software-defined approach helps prevent those flaws from impacting the customer. Based on years of extensive testing, INFINIDAT has learned that typical hardware failures happen within either the first ten days or after five years — the “bathtub curve.” Because of this, each INFINIDAT system goes through a 3-week burn in period prior to shipment to a client. (3) http://www.infinidat.com/blog/automated-testing-the-infinidat-way/ The “Bathtub Curve” illustrating when typical hardware failures occur.

INFINIDAT’s careful approach has required a far greater capital investment and initial time-to-market than other vendors, but has resulted in a pre-integrated, software-defined storage solution that enterprises can truly trust with their most important workloads. INFINIDAT’s InfiniBox is a system with innovative capabilities (over 120 patents filed), that provides high performing, extremely dense, highly reliable storage that is also the most affordable on the market today. INFINIDAT is the single point of contact that owns challenges customers may have with the product in the field. The company is committed to ensure customer uptime. INFINIDAT is able to help clients quickly because we know exactly what goes into our product. You simply can’t get the kind of confidence with software-only SDS. INFINIDAT’s InfiniBox provides high performing, extremely dense, highly reliable storage that is also the most affordable on the market today. INFINIDAT’s hardware-agnostic design enables testing of multiple types of components within our lab environments. As a consumer of high volumes of components, INFINIDAT’s relationships with companies such as Intel and Seagate enable: - Extensive roadmap discussions to determine when new, relevant technologies will be available for the market -Joint brainstorming on new ideas - Regular engineer-to-engineer meetings - Co-development and early access to new components, fostering the next wave of innovation - Joint troubleshooting of complex issues This collaboration ensures INFINIDAT customers get the maximum benefits from all the combined engineering knowledge of the component vendors and our own large engineering staff. Anyone Can Get a Good Deal on Hardware Commodity server hardware is, well, a commodity. Given a particular specification, it’s usually pretty straightforward to negotiate among various suppliers to get a minimum market price for a piece of hardware that meets that specification. Larger clients get better prices, of course, based on volumes. But in a highly competitive server market, the price variance for a given volume of hardware with a certain spec is generally pretty small. That said, INFINIDAT is able to concentrate volume of hundreds of petabytes of customer requests into our rigorous hardware procurement processes for the InfiniBox solution. When we qualify vendors components we look at quality, performance, then price. We only look at performance if quality is good, and only move to pricing if performance is good as well. Further, suppliers that do not provide the best pricing for any one component in the system can be replaced with a similarly qualified supplier for any component, at any time, and several permutations of each component are tested continually in our labs so we maintain that flexibility. We pass these savings directly to our clients. INFINIDAT solutions allow clients to minimize risk and investment versus software-only SDS, while maximizing value derived from their most critical asset: their data. Conclusion The rise of software-defined storage (SDS) marketing is a direct result of legacy storage platforms’ very real struggles with economics and flexibility. However, there are few organizations large enough to allocate the necessary resources to effectively use software-only storage solutions as a true replacement for modern integrated storage solutions. Further, if they do attempt to put together SDS solutions, such organizations often obfuscate or under-represent the true cost of the required resources across all organizational functions. Common errors include failing to account for human resource costs across different business units, ongoing hardware acquisition and testing beyond initial “free” seed platforms (often provided by legacy vendors as a hidden way to ensure future lock-in), and internal support burdens through the full lifecycle of the solution, including upgrades. These errors frequently yield dramatically misleading conclusions about price point and other economic factors associated with software-only storage solutions. Dubious economics aside, software-only storage solutions also bring new operational challenges unique to the category. Software-only storage solutions typically use erasure coding for data protection, sometimes on top of expensive multi-copy replication. While an improvement on traditional hardware RAID, erasure coding is slow during normal operations, and even slower in failure/rebuild scenarios. These performance implications mean that software-only storage solutions must be dramatically overdesigned (with corresponding costs), especially if they are to accommodate a diverse variety of workloads. These operational realities typically relegate software-only storage solutions to Tier 2 or Tier 3 use cases at best. INFINIDAT storage solutions remove these compromises, while addressing the fundamental issues software-only storage solutions try to solve — economics and flexibility. Pre-integrated, software-defined storage from INFINIDAT combines the benefits of software-only SDS with the lessons that come from over a century of experience designing and implementing solutions that have defined the storage industry. INFINIDAT delivers a new choice in the market: storage that is ultra-flexible, high performance, and capable of delivering 7x9s resiliency with economics that are disruptive to both legacy proprietary storage platforms and the build-your-own, SDS approach. Contact INFINIDAT to learn more about how INFINIDAT storage solutions minimize risk and cost for next-generation storage requirements.